TAP TO ENLARGE

![los caprichos [text by Goya]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5615c191e4b0752eb58283fa/1637871838973-LUG4PD9CY5W239T0ZN9K/109+GRIMOIRE.jpg)

LORD [stop] OF [stop] LIFE [stop] REMEMBER US

A Note on Grand Grimoire

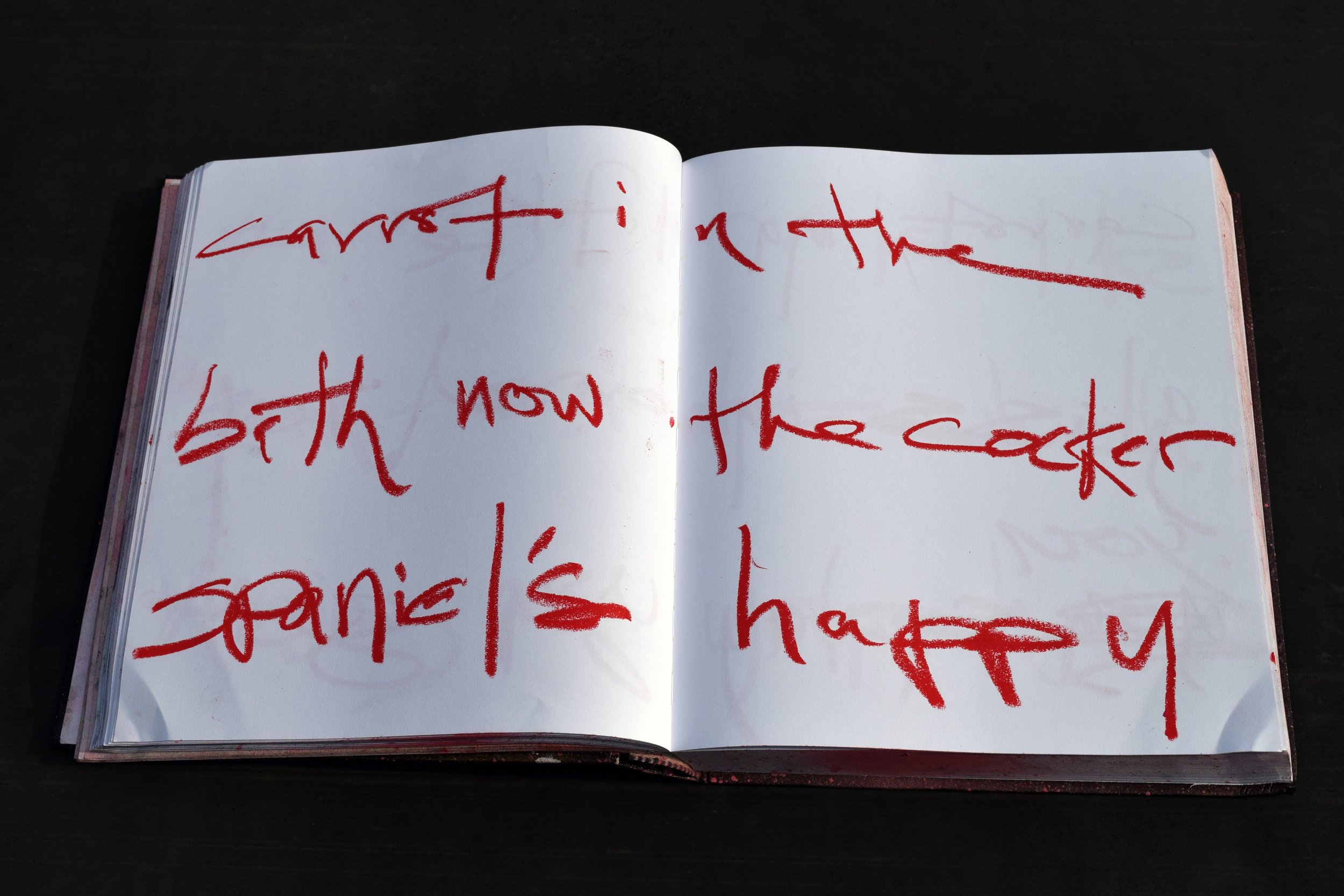

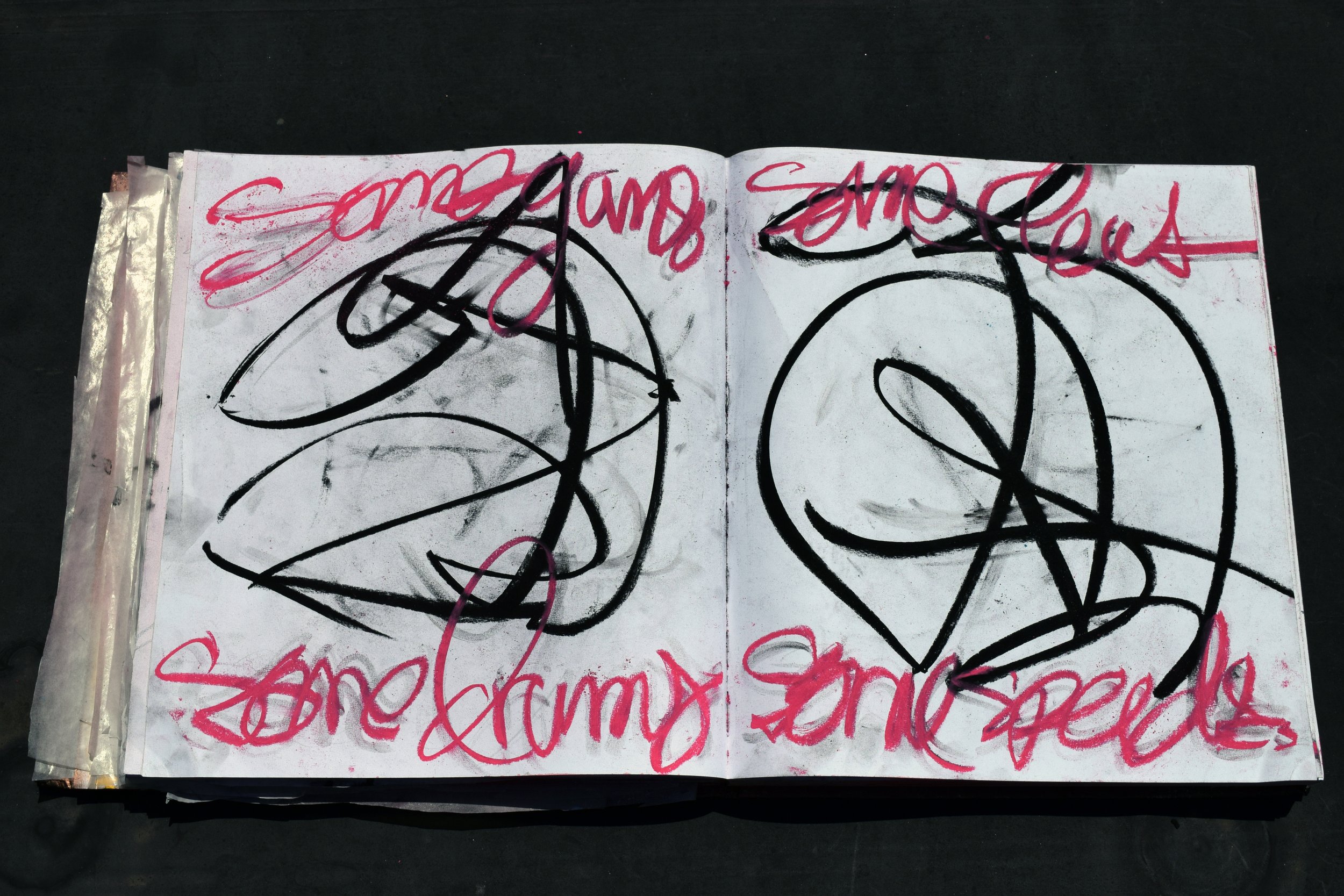

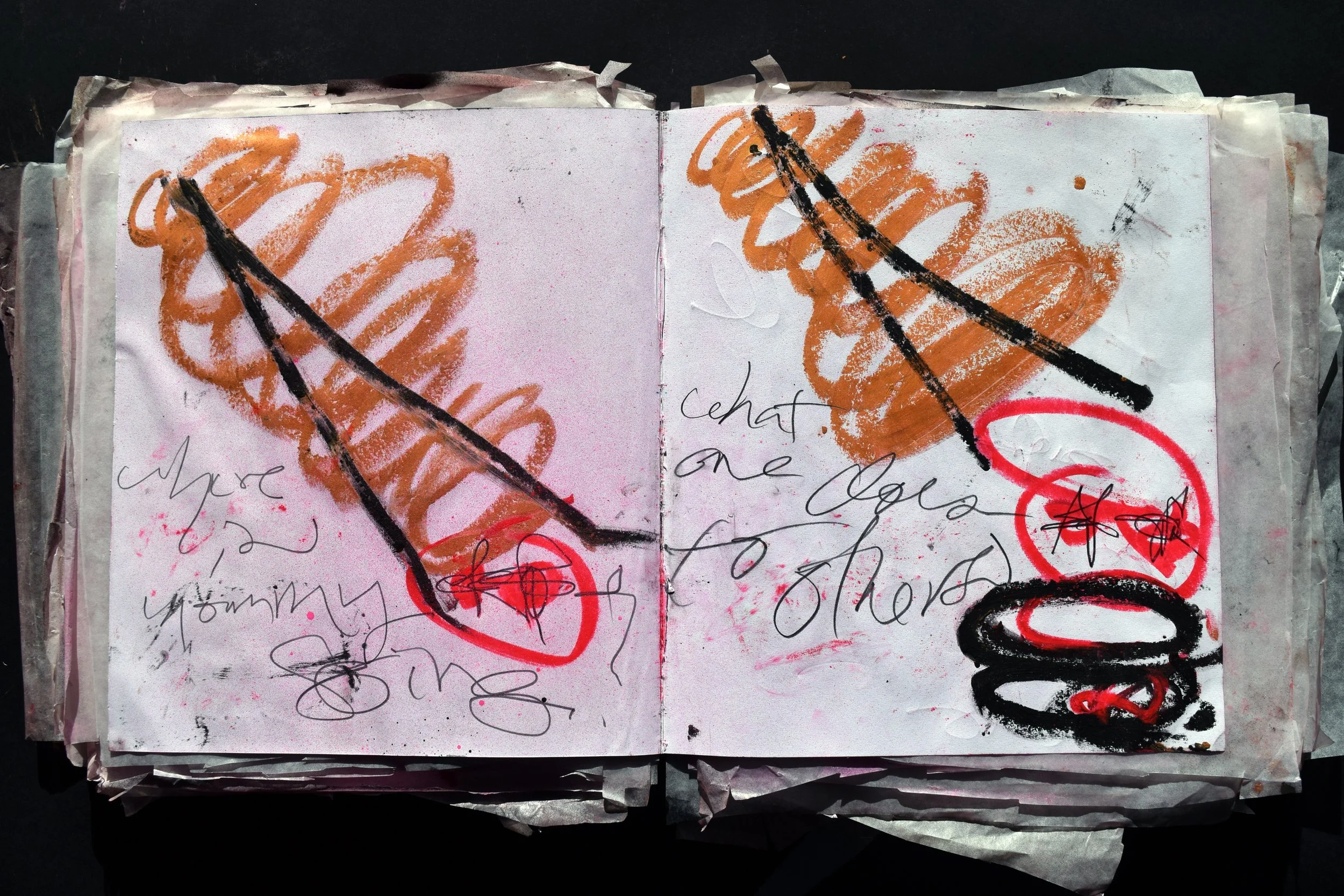

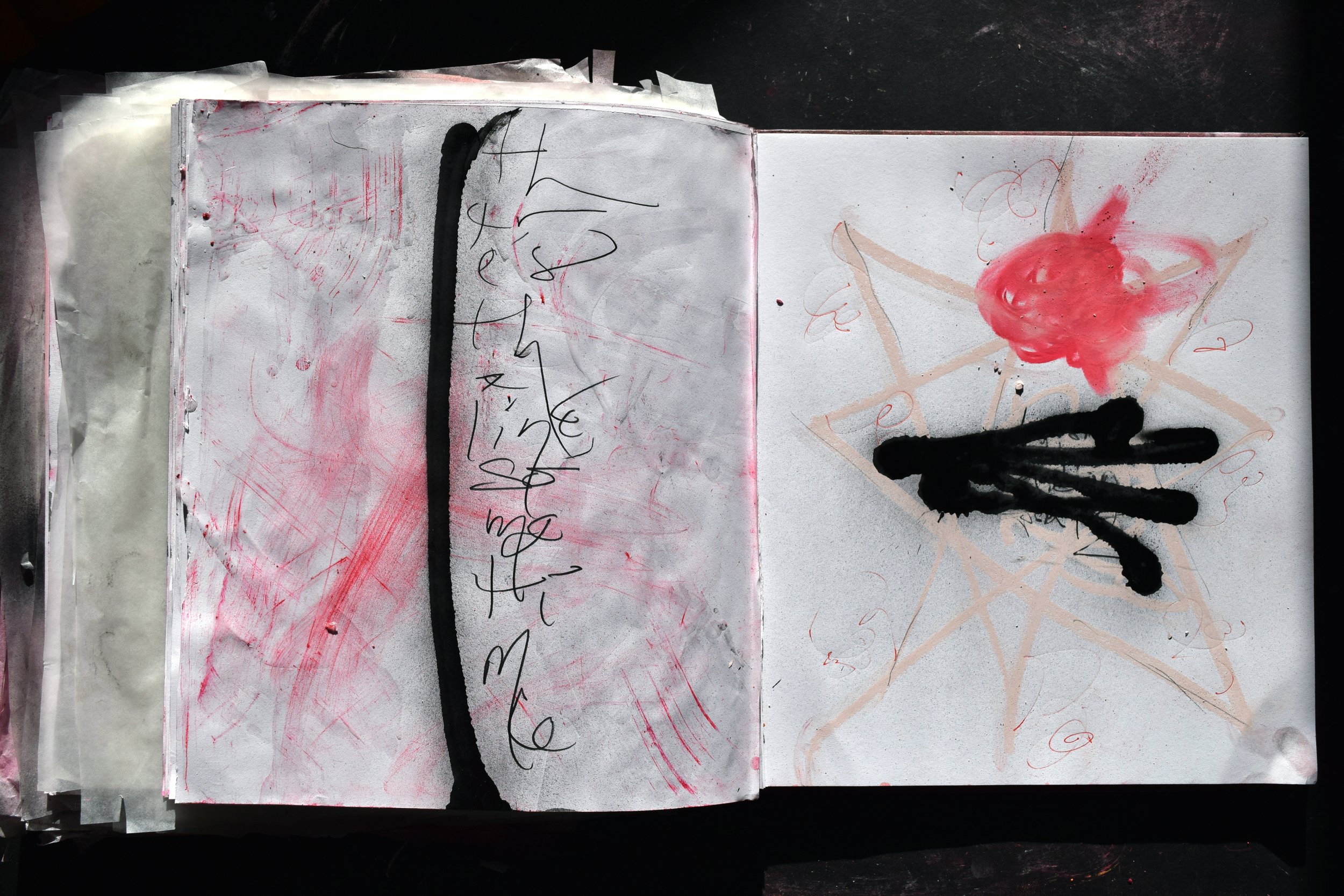

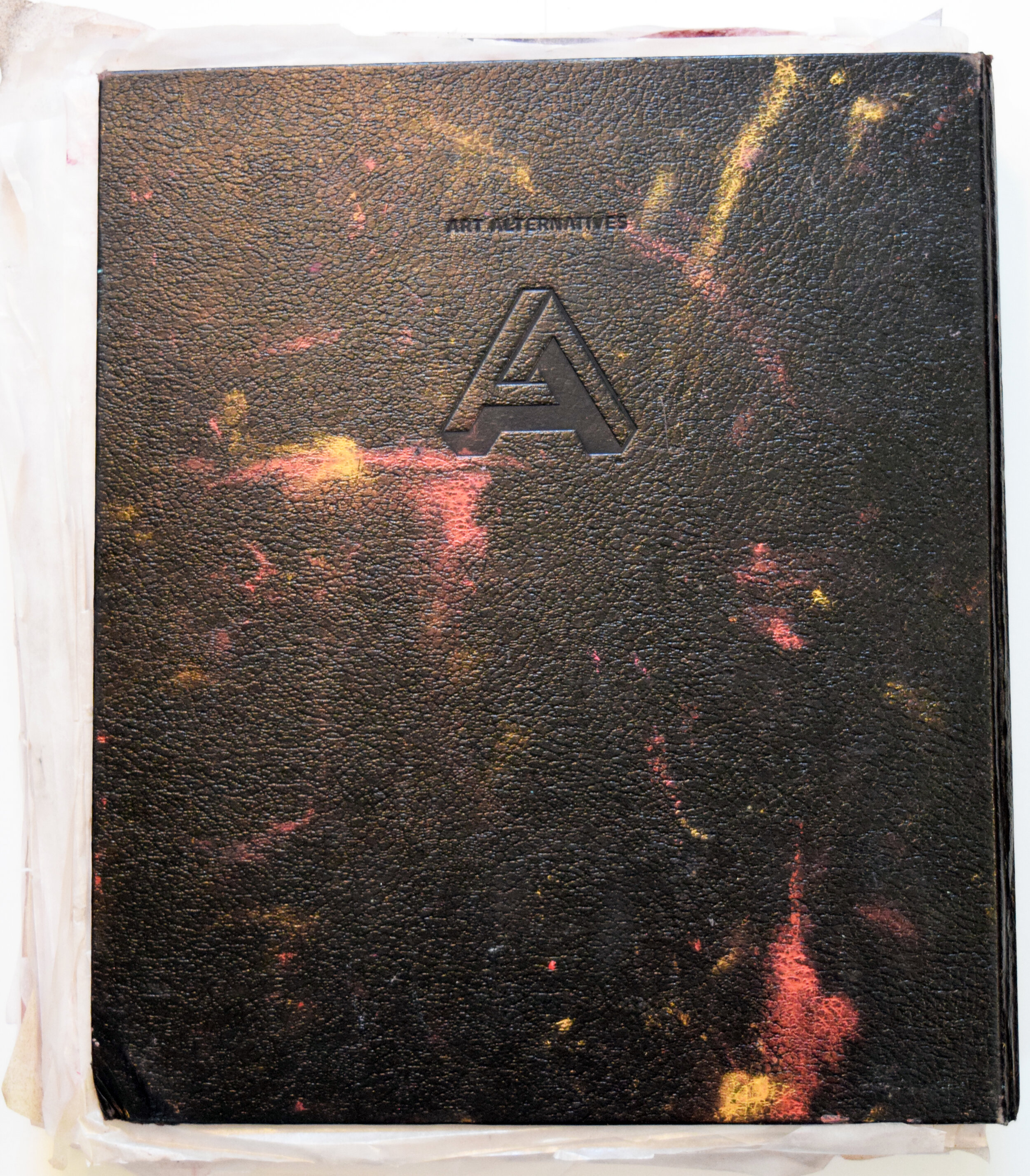

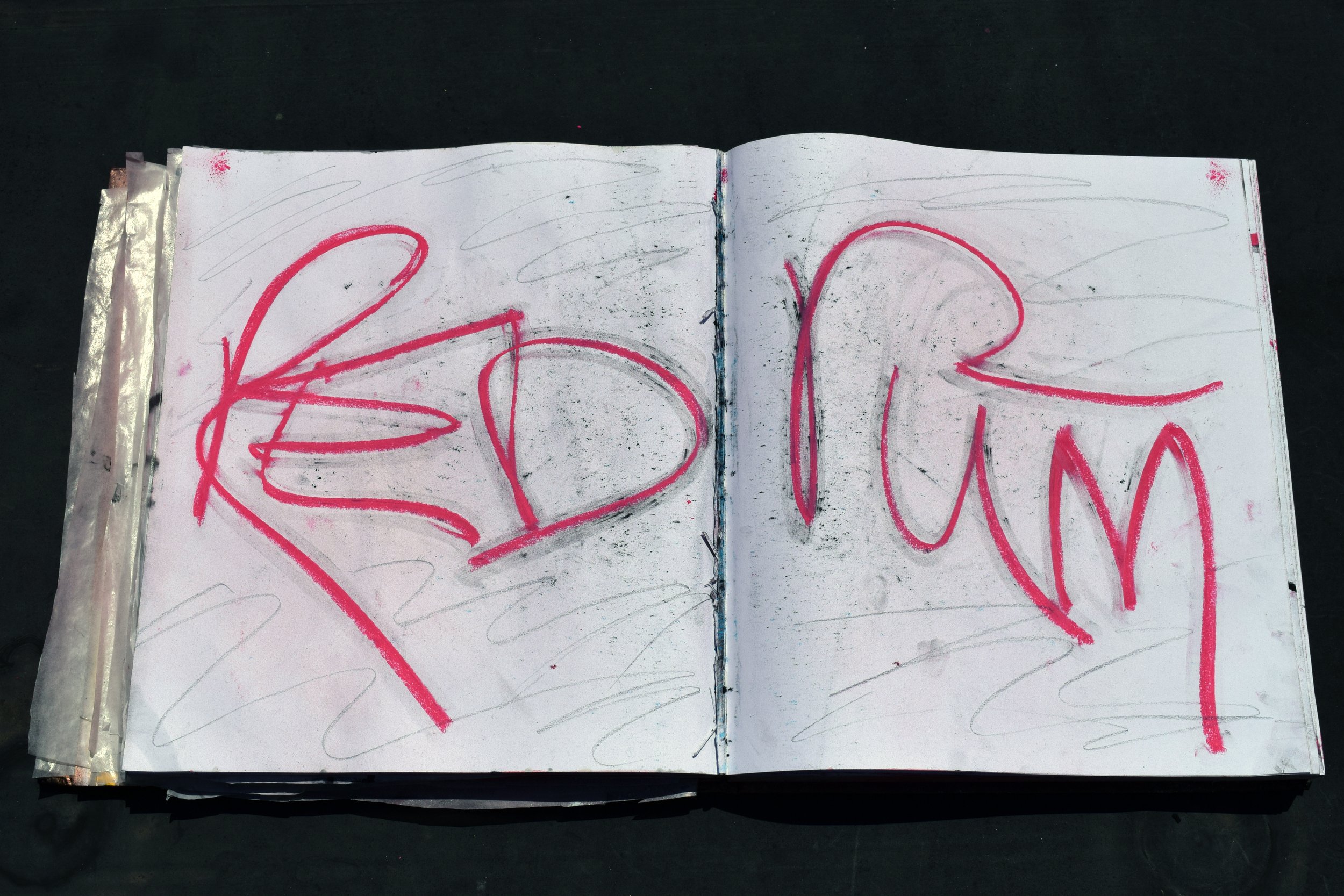

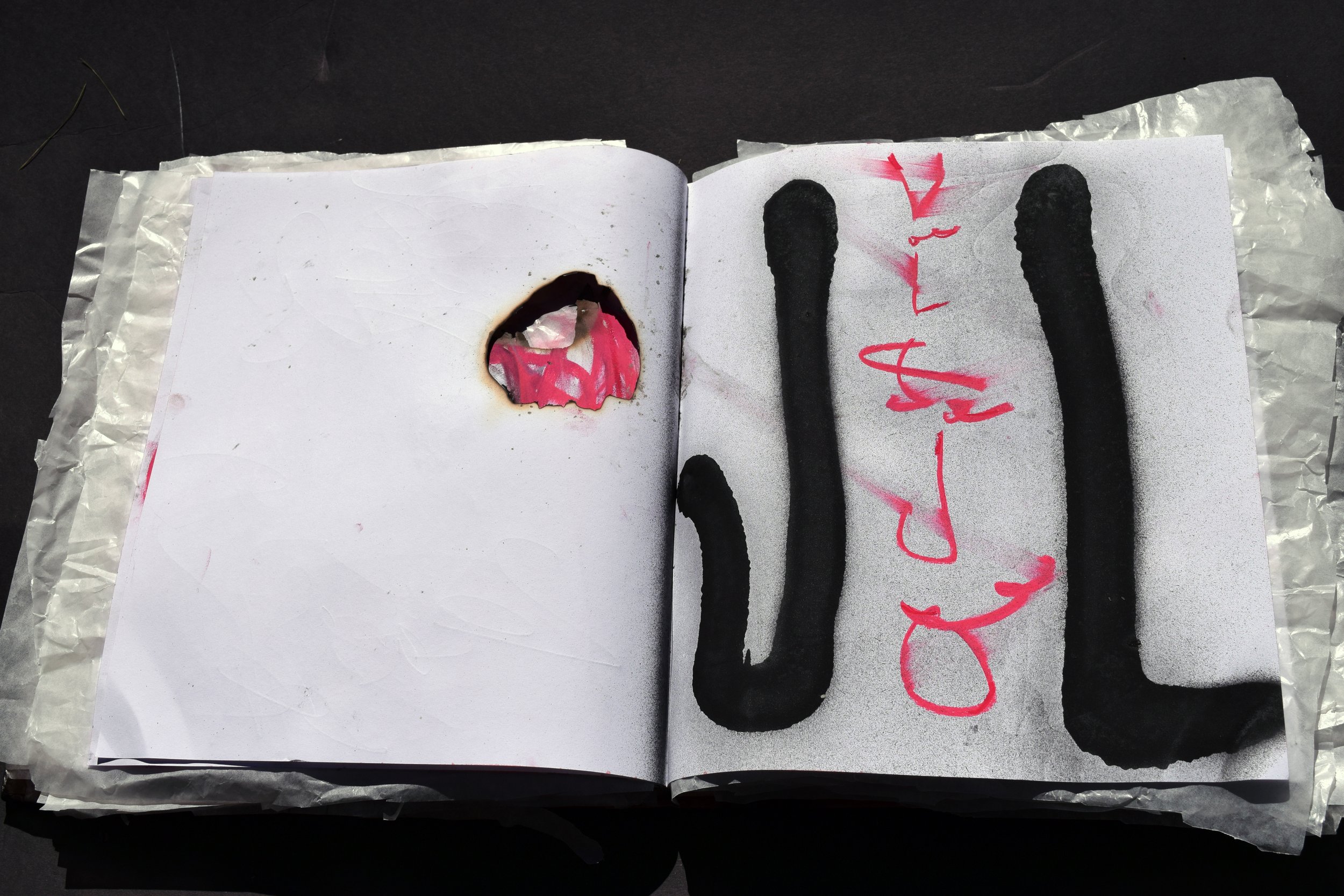

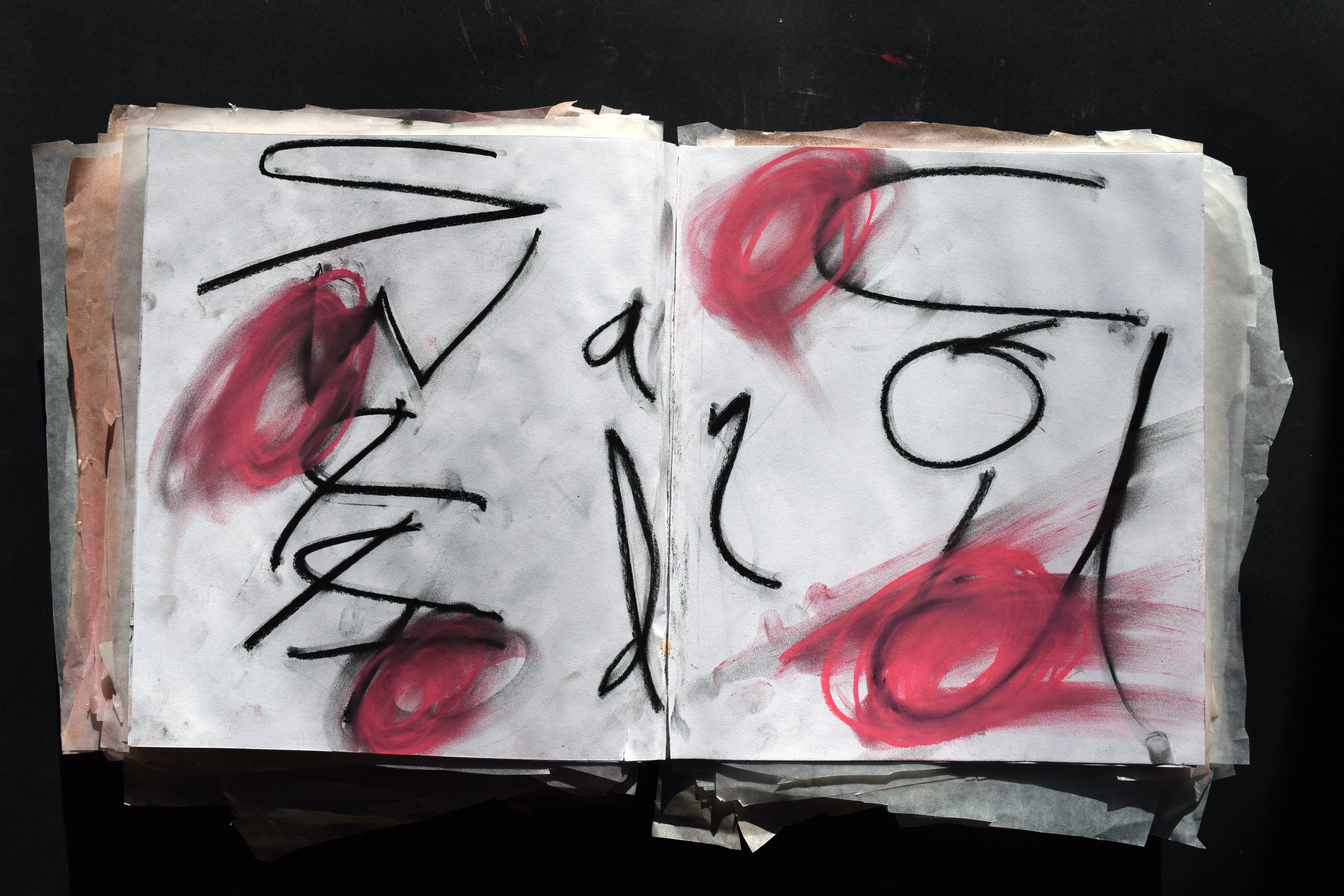

Grand Grimoire’s support is a 12.5 X 10.75 inch Art Alternatives Very Big Sketch Book, which can be purchased at art stores and online. The Very Big Sketch Book reads as an item of interest to both amateur and professional, broke college kid and someone with disposable income. “Sourced from sustainable forests,” it costs around $30, but its heft and austere black cover give it the look of something more expensive.

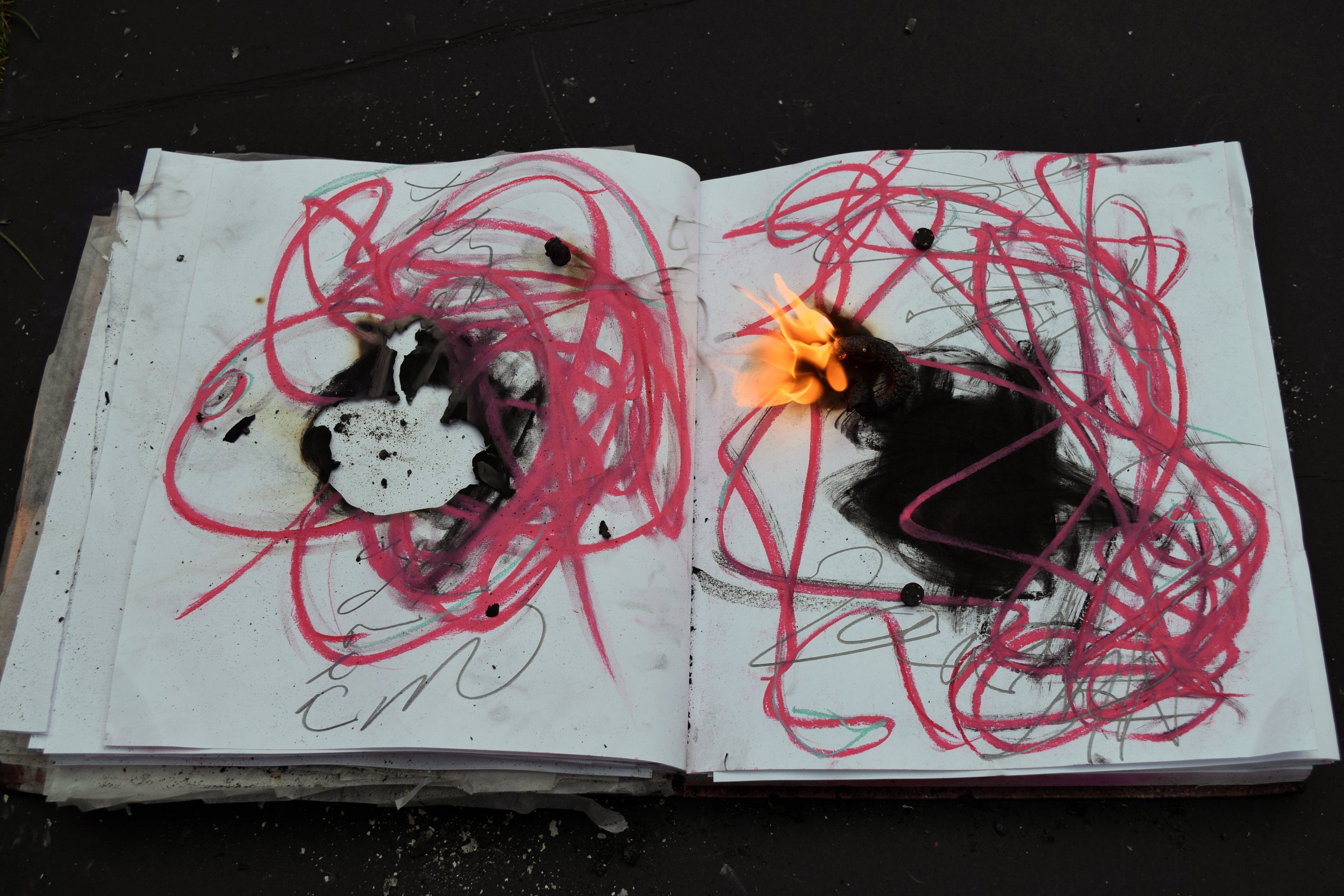

I offer this description because the object itself, with its simultaneous potentials for professionalism and dilettantism, conditioned the composition of the sequences in Grand Grimoire. Composing in the book was a precarious process, and early on I disposed of several books because sequences were not working or I made unrecoverable errors. After making substantial progress, however, I had to treat it as a singular object—a record of traces that could not be repeated.

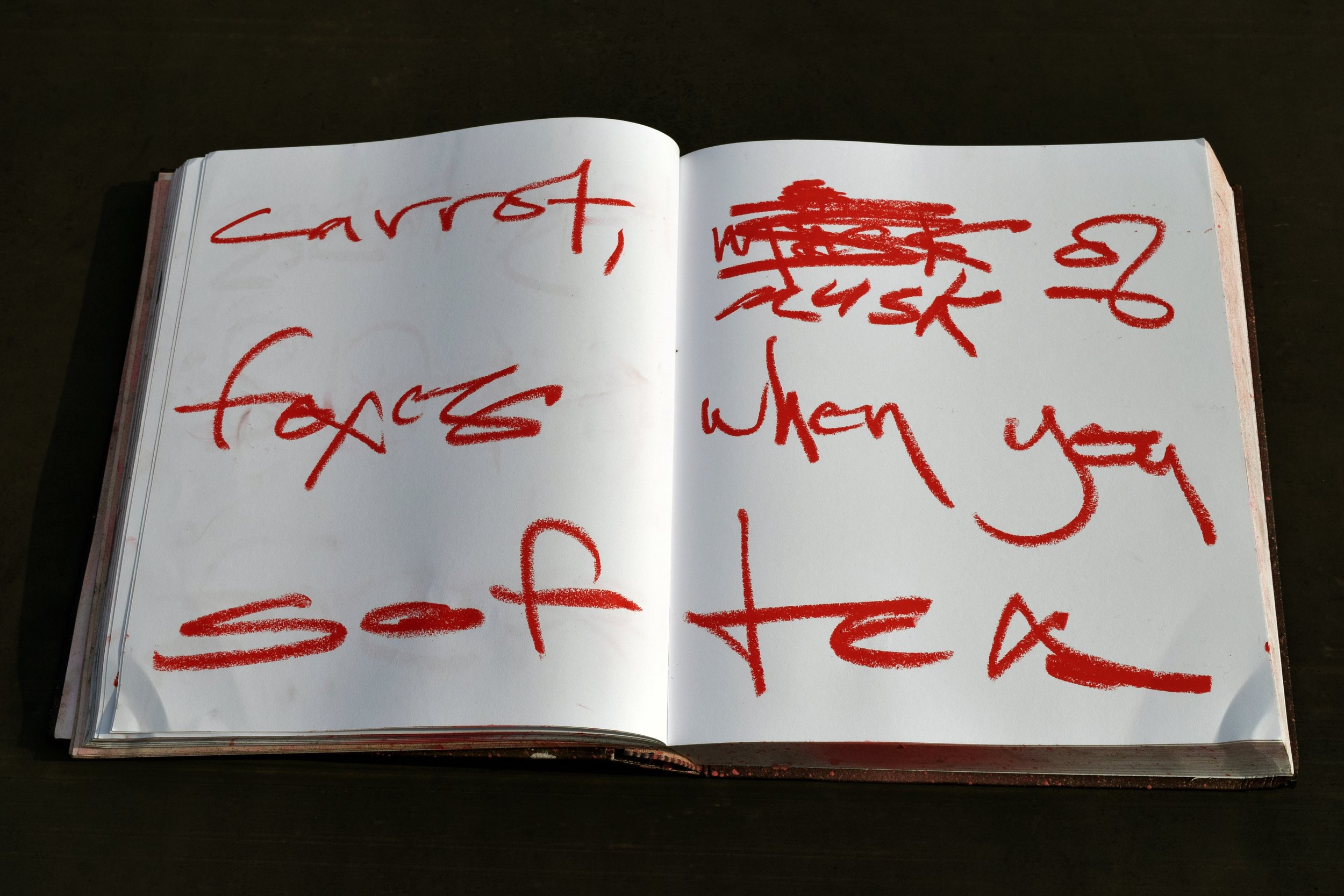

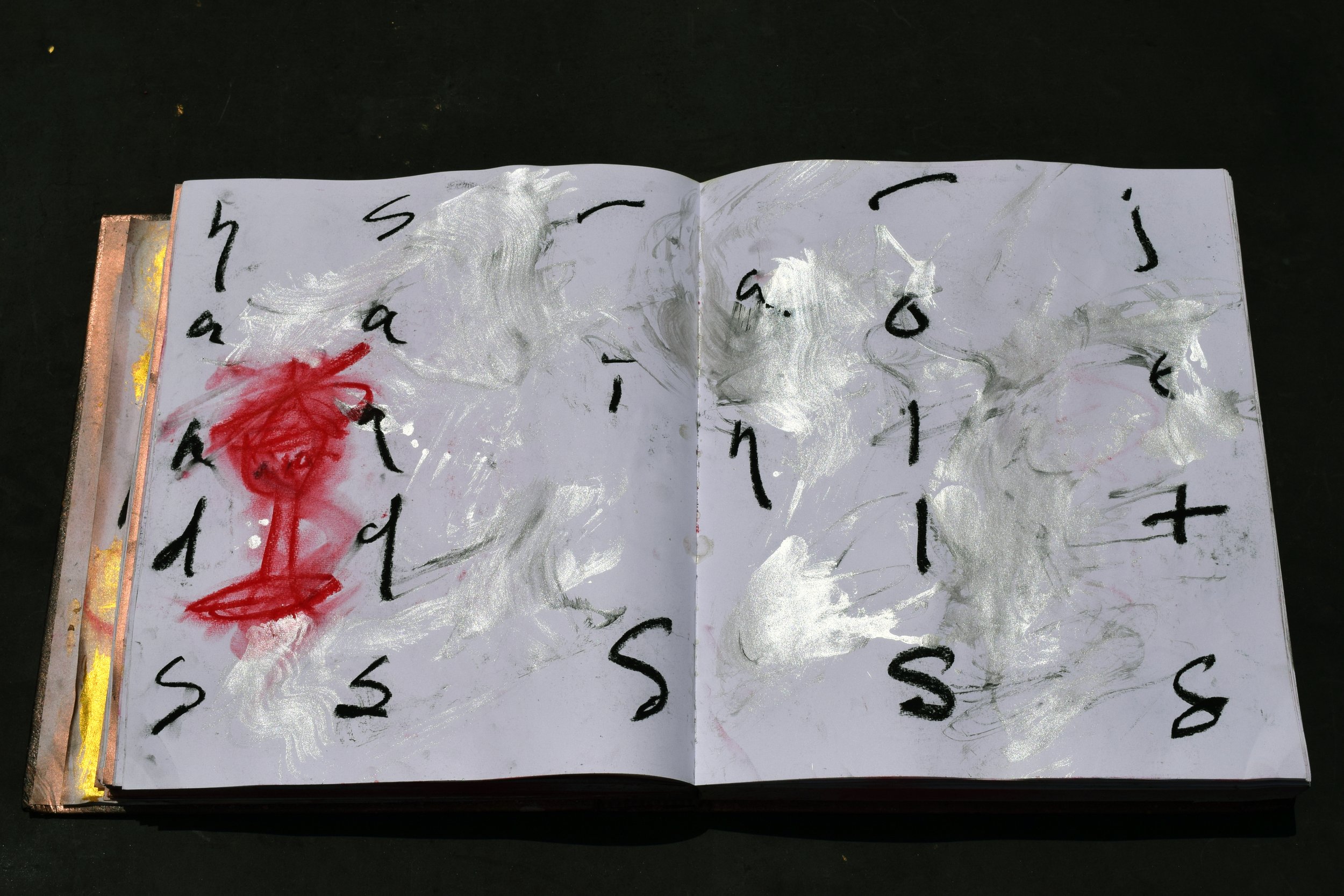

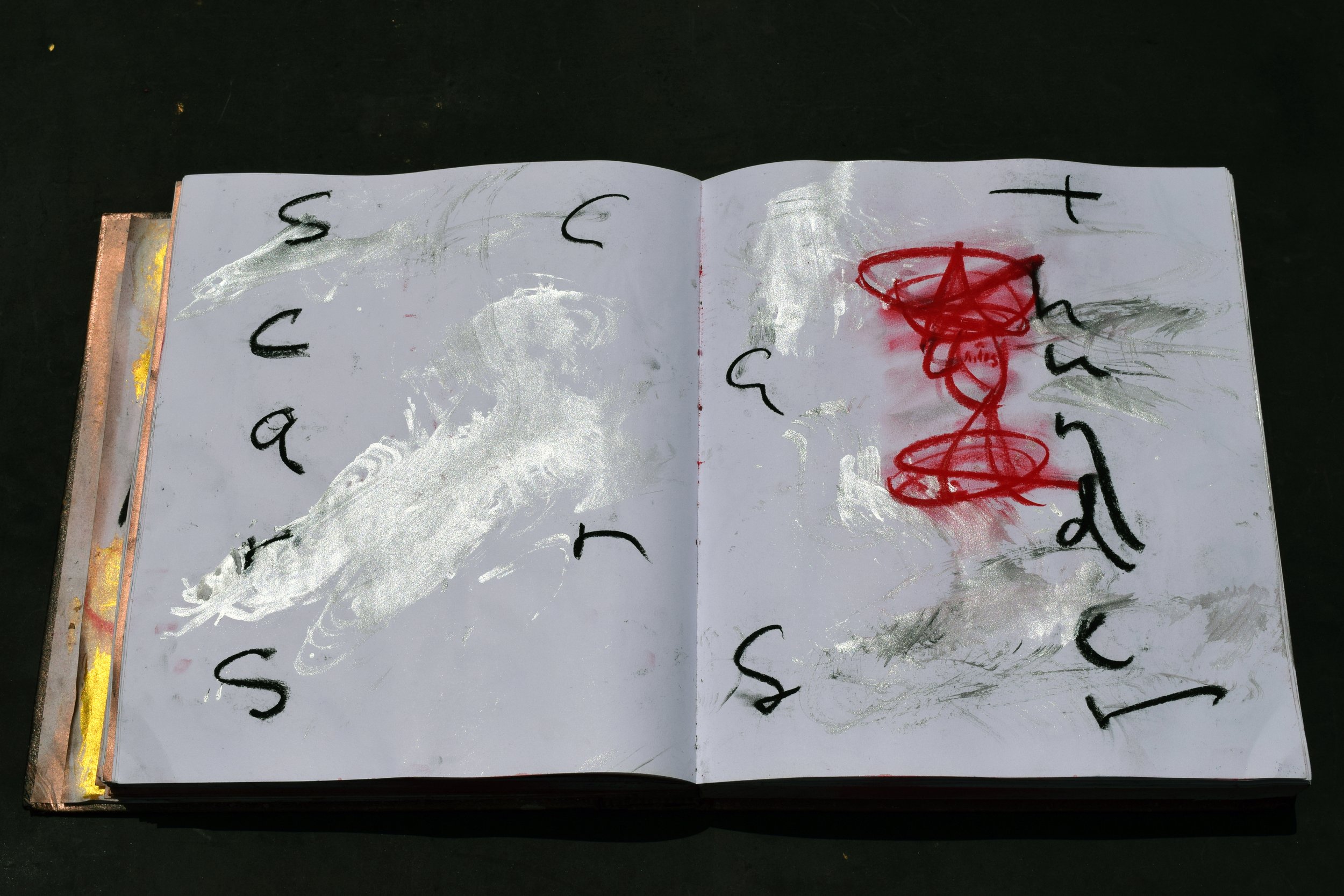

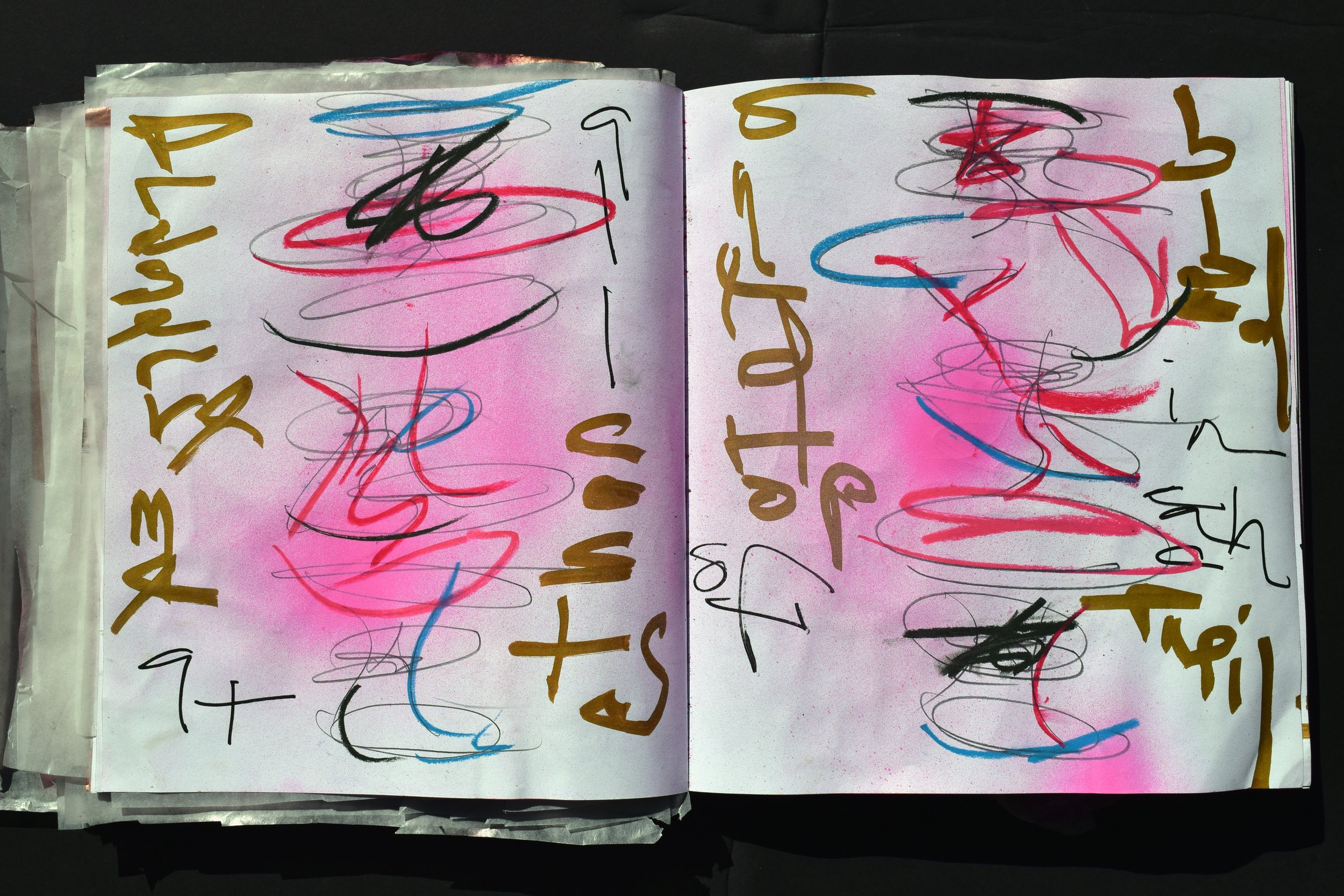

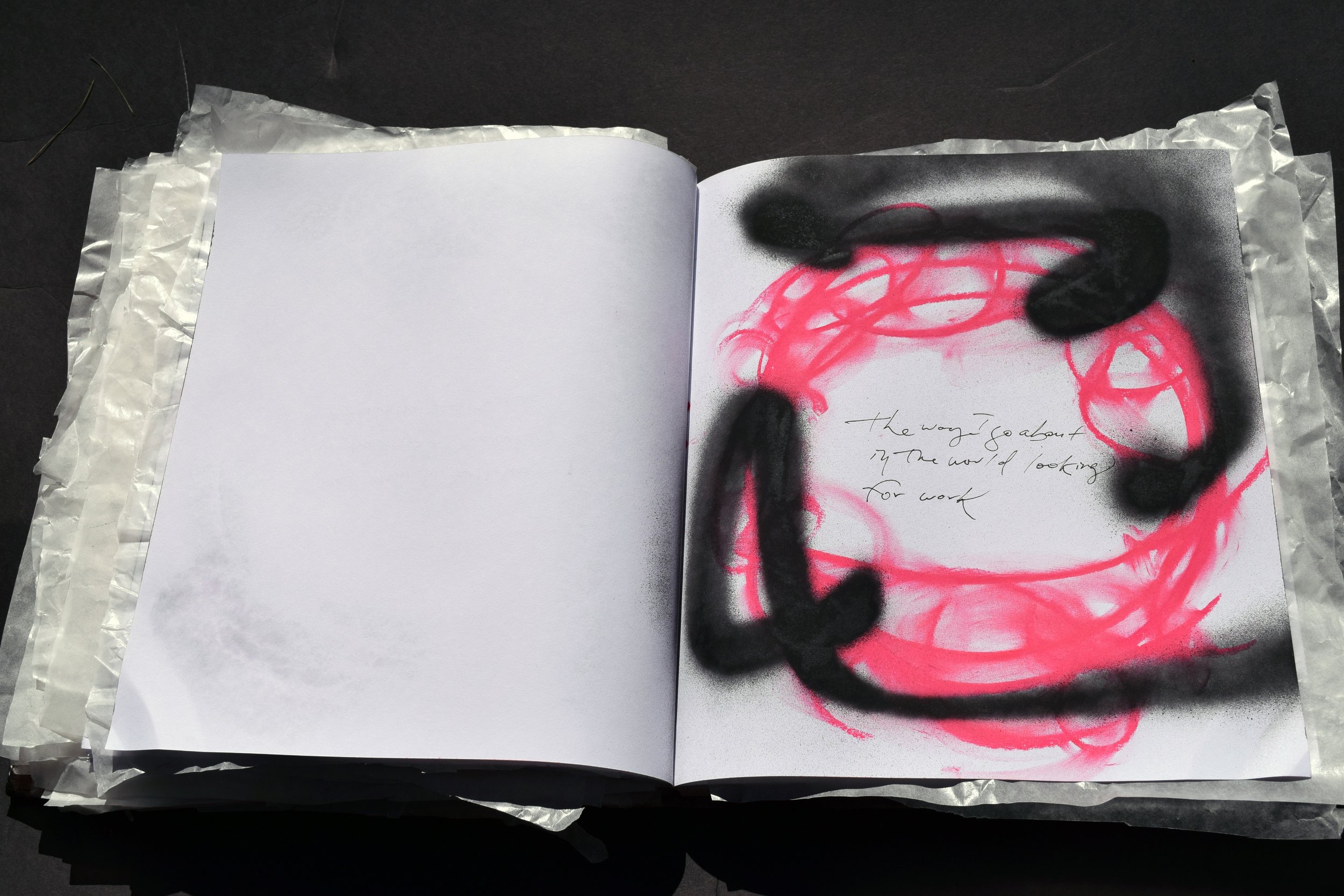

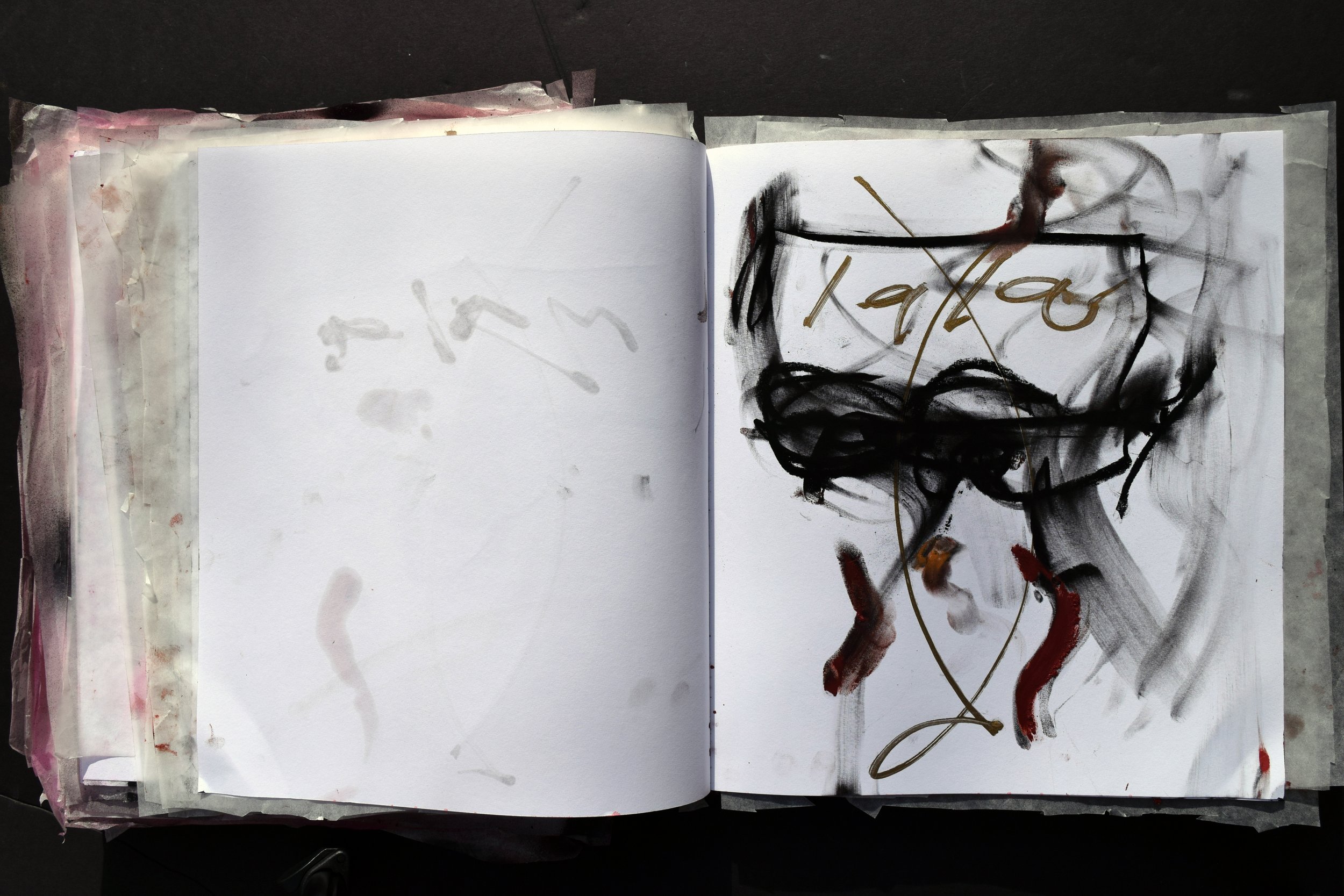

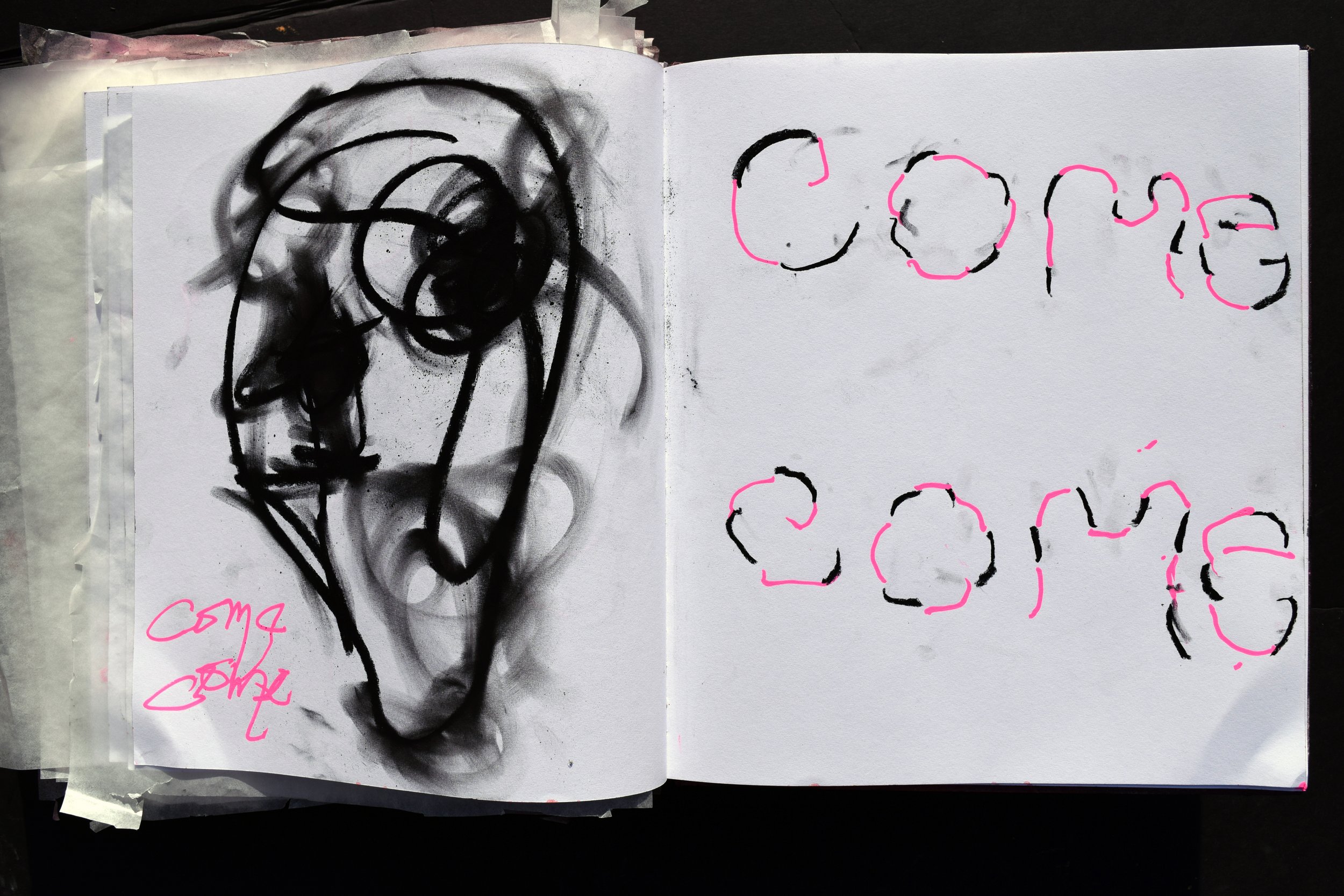

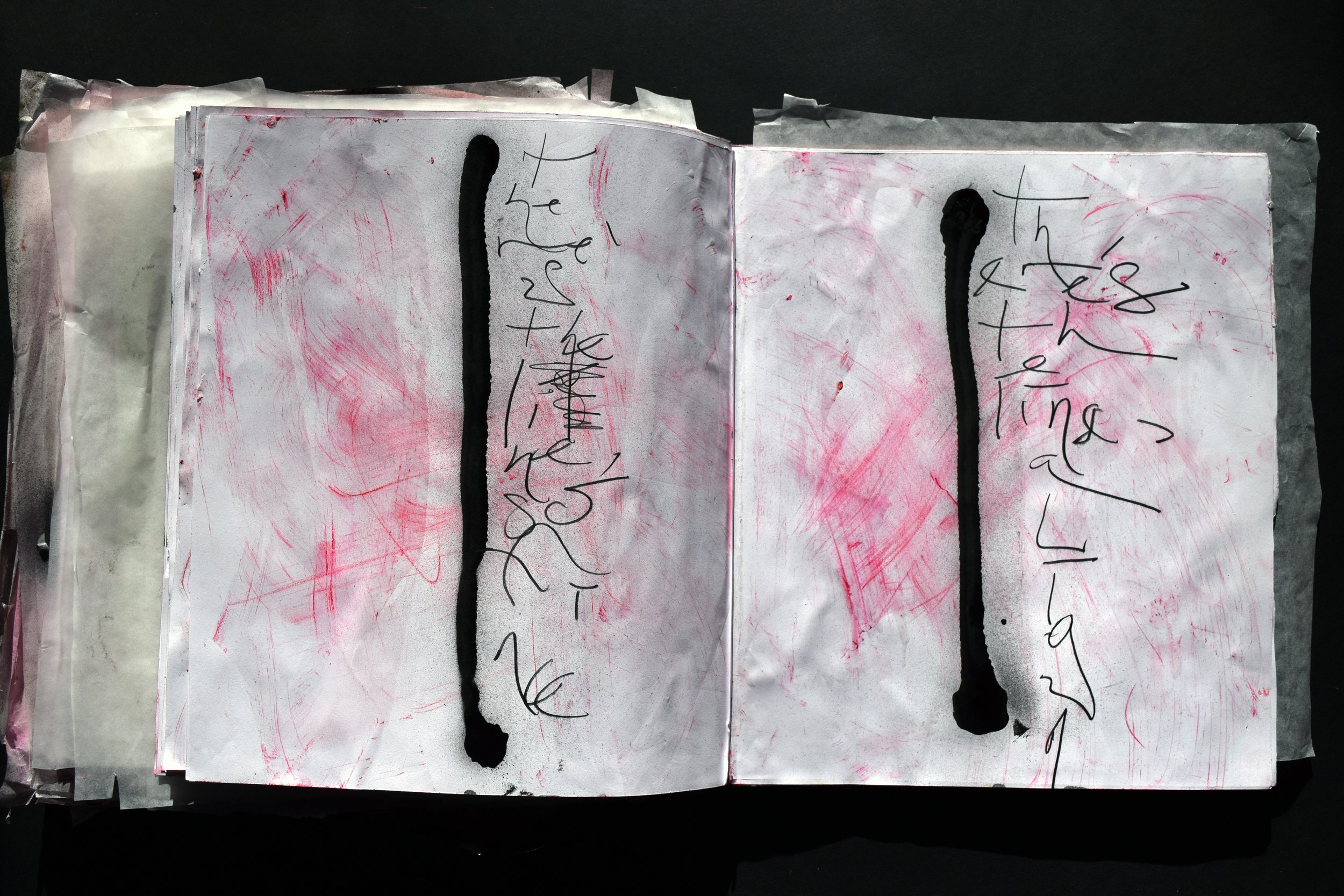

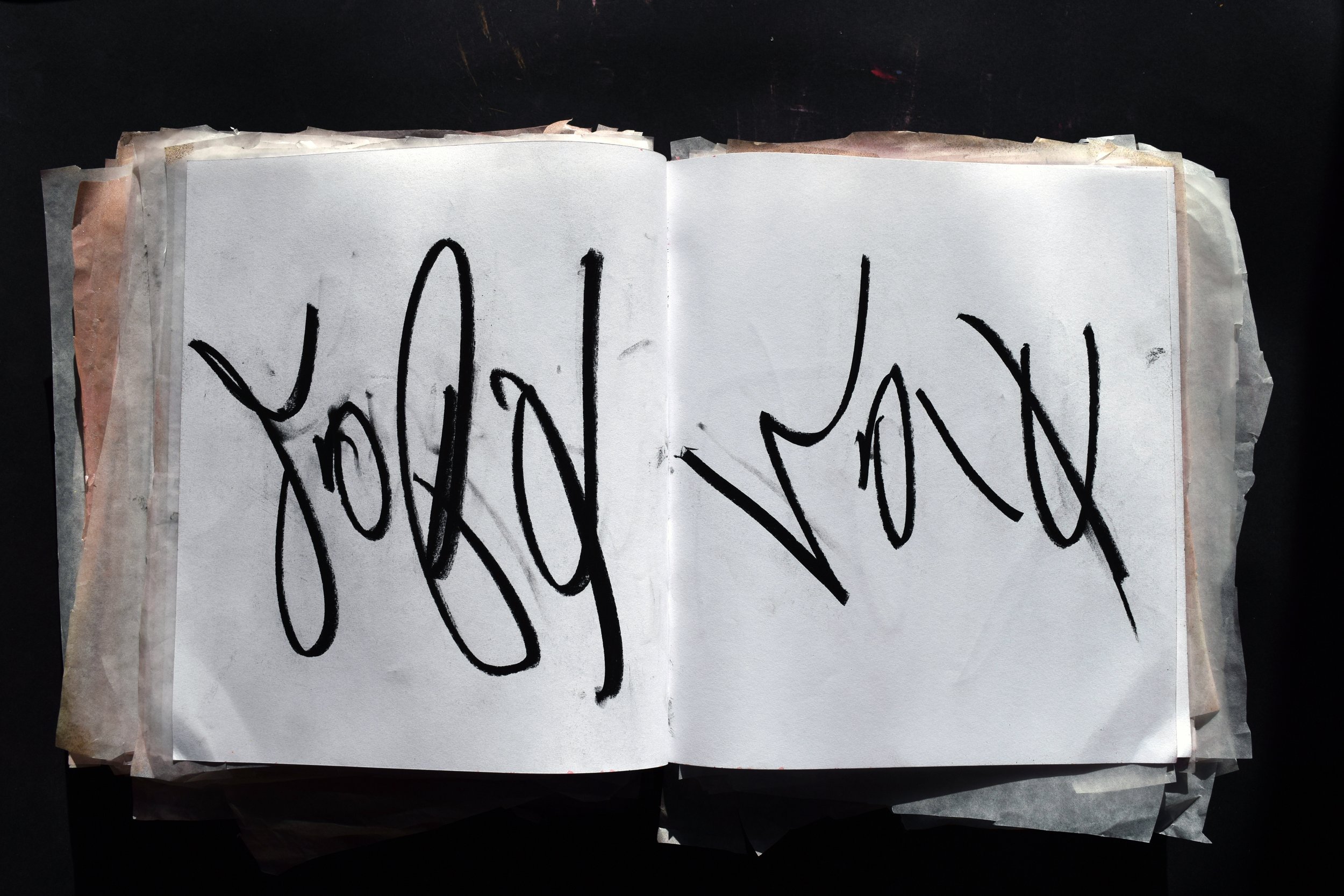

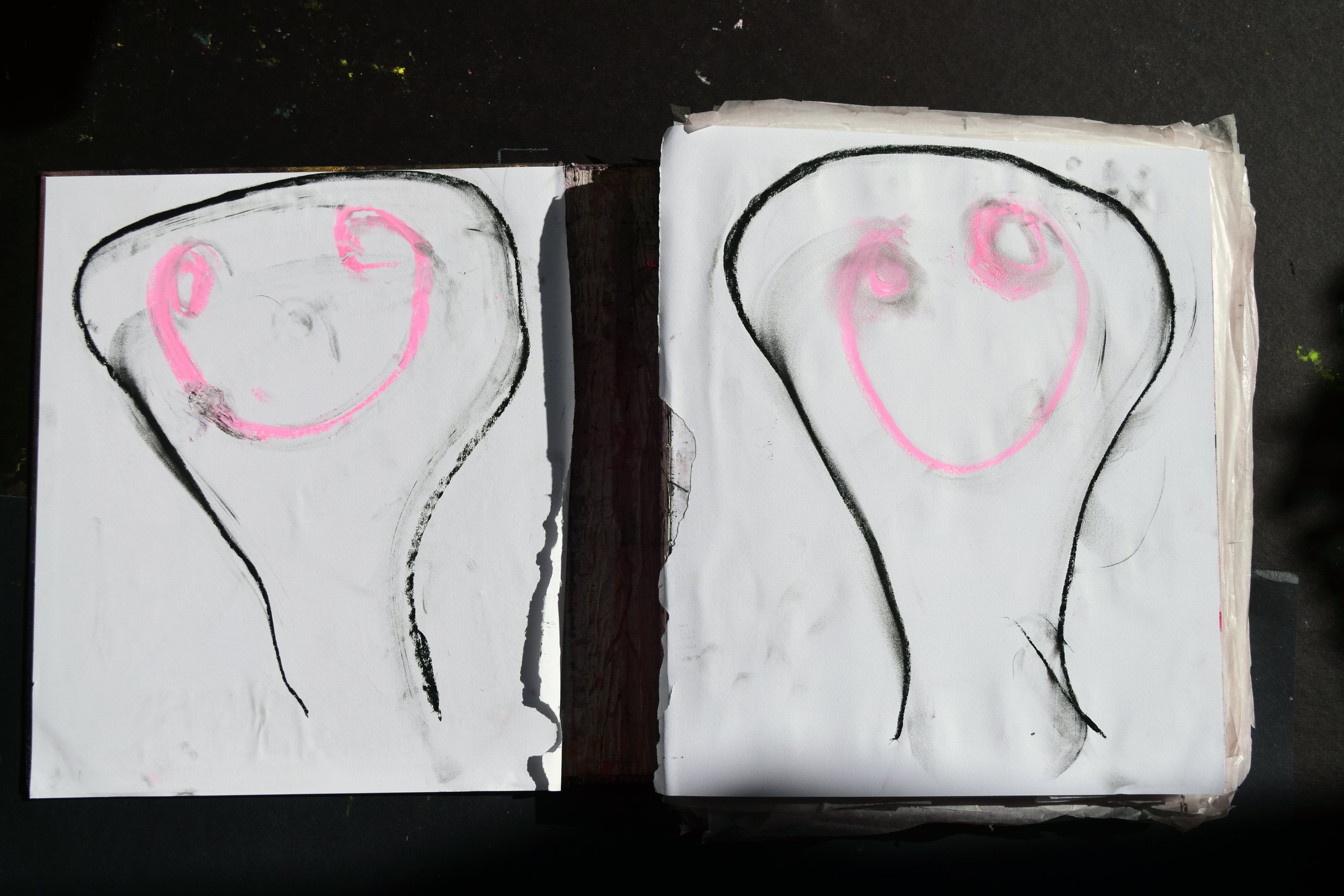

Nevertheless, I tried throughout to preserve the spirit of play and irreverence made possible by the book’s inexpensive nature. This oscillation between the sacred and the profane, the singular and disposable, is heightened by tensions between the various genres the book draws on—illuminated manuscripts, spell books, fine art, love notes, doodles, graffiti, and so on. Central to the visual dynamics of the book is my handwriting, which moves between a scrawl and glyphs and anchors and feeds the other elements on the page.

Reading a handwritten text requires more of a reader than a printed text, as does reading text in the context of surrounding images, as does reading a handwritten poem that turns into images and vice versa. As such, it may be tempting to treat Grand Grimoire as a book of images and to read the poems in transcription. I hope, however, that the sequences will, when possible, be read as singular works.

Making work within the horizon of the Very Big Art Book’s constraints has meant, among other things, composing on the spot to keep the gesture unselfconscious, learning to compose with finite available physical space, writing while foregrounding questions of structure like placement, readability, and busyness, and qualities like color, texture, and depth, and keeping both semantic and visual relationships across the entire book in mind while composing.

Among the genres informing the poems are praise, lamentation, and recrimination lyrics. There is the ode, “carrots,” to carrots, the mournful “coca,” about the effects of the drug trade in the 80s, and the recriminatory “vrykolakas,” or “vampire” in Greek. Throughout, the question of life—biological and lived life—is at stake. For instance, the book ends with the series “Anyte” (after the Greek poet Anyte, who often wrote about animals), and mixes anatomy, animals, and drugs in a hymn to life’s tangled mix of technologies, forms, and chemicals.

Grand Grimoire is an example of what I’m calling The Chimeras—ongoing paintings, drawings, art books, notebooks, videos, stills, photographs, photographed object sequences, objects, etcetera that fuse images and text. I would say that where The Chimeras depart from other visual-textual work is in the desire to explore more fully the possibilities nontraditional media and supports offer for writing poems.

—Robert Fernandez